SWING AND A HIT

Author(s): Douglas Belkin Globe Staff Date: June 16, 2005 Page: 1 Section: Globe NorthWest

GROTON - If the script had been written in Hollywood, the hard-cutting screwball that Mike Kane had been torturing hitters with all afternoon would have remained untouchable right through the championship game.

This Wiffle ball tournament was, after all, a memorial to his brother who was killed in a car crash seven years ago. So as Kane and his teammates outdistanced all but four of the 96 teams by running off seven straight wins to earn a spot in The Brian Kane Memorial Tournament semifinals, he was the sentimental favorite. But this script was not written in Hollywood; it was written in Groton, and the New England-based team that Kane faced the same one that beat him last year in the finals was not just any old team. It was "Doom." In a field of players dressed in cut-off shorts and paint-splattered tank tops, Doom members wore color-coordinated uniforms with the letter D on their hats. They carried their own Wiffle ball equipment in canvas bags. And all their players had traveled the nation like the baseball barnstormers of old, winning tournaments, crushing dreams, and putting backyard pretenders squarely in their place.

Last year they earned $20,000 in prize money by winning 39 tournaments. This year they are ranked second in the nation.

Kane's screwball didn't have a chance. Final Score: Doom 12, Hometown Favorites 1. Doom went on to win the tournament.

"I don't really think of this as a hobby so much as a part-time job," said Adam Trotta, a Doom pitcher who threw a sweeping curveball that was virtually unhittable. "We play all the time. We're serious about this."

Welcome to the new Wiffle ball. That once casual New England backyard pastime has grown up and gone big time.

Fueled by baby boomers' latent nostalgia for the game, a cult-like devotion to the competition and a thriving Internet community that has enabled far-flung players to connect and organize, Wiffle ball has quietly supersized into a sport that bears little similarity to the game many Americans grew up with.

While the ball can still be a staple in friendly pickup games between two sets of neighborhood 10-year-olds, there now are also seasoned 30- and 40-something adults training to earn a berth in the world championship in Texas. There is substantial prize money at stake, indoor winter leagues to hone skills, and dedicated fields complete with night lighting on which to compete.

And the funky pitches of yesteryear that used to arc lazily toward the hitter have been supplanted by cut fastballs so vicious they can whiz by the plate at 70 miles an hour from a pitcher's mound 40 feet away all while breaking 2 1/2 feet across and rising.

"Last year I faced that kid and I swear the ball touched the grass before it came by me for a strike," said Mike Flynn, who grew up playing Wiffle ball with the Kane family, and whose team was knocked out in the early playoff rounds. The "kid" he was talking about was Trotta. He is 32 and a supervisor at the Massachusetts Department of Youth Services.

"When you watch him, you realized they're pretty much playing a whole other game," Flynn said.

Across the country, from Billerica to San Diego, enthusiasts have built their own backyard diamonds in New England, many have fake Green Monsters in left field like Fenway Park. And in the last five years previously informal gatherings have morphed into highly competitive federations. There is the Golden Stick Wiffle Ball League on the North Shore, the New England Wiffle Association in Worcester, and Fast Plastic, based out of Rehoboth, which started running the national championship tournament in Texas three years ago.

"It's kind of like an underground community like Fight Club," said Mark Spellman, 28, who plays for Doom and several other teams even though he can no longer pitch because he ripped his rotator cuff pitching three years ago. "Sometimes I think it's kind of like a cult."

This year, teams from 14 regions in the country each fielding three players at a time will meet in Texas for the Fast Plastic national championship. The prize money will be $6,000. Bruce Chrystie, 41, the executive director, predicts the pot will climb next year to $30,000. Regional champions have their air fare covered by the tournament.

"It's just taken off in the past couple of years," Chrystie said. "The people who are into it are just really into it."

In the same way that dodge ball morphed from an elementary school gym class activity to a competitive sport with rules and a governing body, ad hoc Wiffle ball rules have been standardized.

In the modern game the strike zone is 23 inches wide by 27 inches tall and defined by a backstop set 13 inches above the ground. Center field is at least 80 feet from home plate and the foul poles are at least 70 feet down each line. Depending on the pitching speed, the ball is thrown from between 30 and 50 feet away from the batter. And as has always been the case in Wiffle ball, there are no base runners. Hits are determined by where a ball lands on the field. An out is made when the pitcher or one of the two defensive players fields the ball cleanly.

The game has come a long way from the early 1950s, when Dave Mullany started fiddling with hollow plastic balls to make it easier for his son to throw a curve in his backyard pickup games. The design he came up with, which incorporated eight oval holes on one side and none on the other, produced a sphere so unstable that just a soft toss and a little spin produced a notable break.

In the Connecticut neighborhood where the Mullanys lived, a strikeout was called a whiff. When the ball was taken outside for its first game it sailed past most of the hitters and the Wiffle ball was born, said Mullany's grandson, David J. Mullany, who is today the company president.

By the mid-1950s Mullany, whose car-polish company had recently failed, took out a second mortgage on his house to mass-produce the balls. A few years later, Woolworth began carrying the ball and the yellow plastic bat. By the early 1960s a backyard tradition was taking root across the country.

One of the kids who picked up that plastic ball and bat was a boy in Arlington named John Kane. Kane grew up, married, became a father, and in 1983 moved to Groton, where he taught his three sons to play Wiffle ball. In short order he built a stadium in the backyard and the Kanes and whoever else was around from the neighborhood played through the summers.

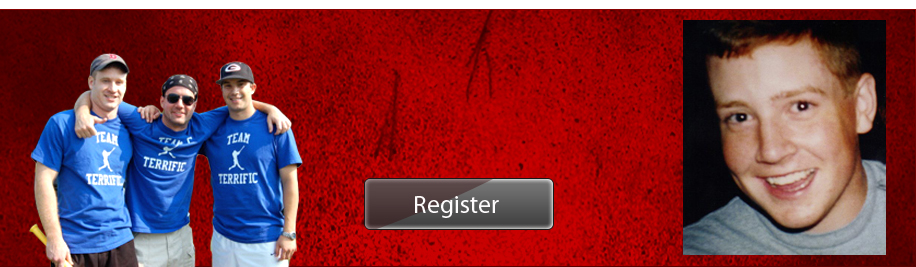

Then, in November 1998, John Kane's second son, Brian, a well-liked 18-year-old, was riding home from hockey practice with a friend who had just gotten his driver's license. The friend was speeding and lost control of the car. It slid off the road and slammed into a tree stump.

John Kane was at a friend's house playing cards when he got a call around 8:30 at night. "At first all they told me was that something had happened to Brian," he said on Friday. He soon found out his son was pronounced dead at the scene of the crash.

"You don't really get over something like this," John Kane said. "You just get better at adjusting."

The Kane tournament is part of that adjustment. In six years it has grown from 40 teams to 96. On Saturday players came from as far away as Ohio to compete and it felt like half of Groton turned out to support the event.

While its purpose is to fund a scholarship in Brian's memory awarded to a graduating high school senior from Groton the coin of the realm on game day is pitching, and there is nothing sentimental about how the game is played. Indeed, by the time the sun was heading down there were dozens of cracked and bent yellow plastic Wiffle ball bats discarded after they had been hurled into the ground in frustration.

"It kind of reminds me of golf, the way it gets people so crazy," Spellman said.

Teenagers in the tournament didn't last long. Play was dominated by seasoned 20- and 30-somethings. And Kane's team, behind his inscrutable screwball, seemed destined to take the trophy home until it faced Doom.

"Unbelievable," Kane muttered after striking out.

"These guys are unreal," said Anthony O'Connor, Kane's teammate, as he watched the game slip away.

Chrystie, of Fast Plastic, looked on with admiration at Doom's lineup. "Yeah, they can play," he said. Then he started talking about his son, who had taken a few swings with a Wiffle ball bat in his backyard last week.

"I'm telling you," he said, momentarily taking his eye off the game. "He's only 5, but the kid's a natural."

The 2013 Brian Kane Memorial Scholarship Tournament will be held on June 8, 2013 beginning at 9AM at the Groton-Dunstable Regional Middle School. Sign-up now!